An examination of zero to one problems in maritime tech

Hrishi Olickel

Published on 19th Oct 2022

7 minutes read

Maritime technology has come far as an industry - but I'm often surprised at the lack of companies in the space, given how large and inextricable shipping is to the modern world. When Greywing started, the field had few players, especially in maritime operations. There are a lot more of us today, but far less than you might expect.

It isn't a lack of fruitful problems to solve. I have covered the reasons maritime needs technology before, and all of those reasons still hold water. It's certainly not a lack of talent, or application. In a world where engineers look to have real impact on tangible industries, shipping feels like a strong place to work. So why indeed?

Some of the more obvious reasons might be that shipping requires domain knowledge that may be hard to come by, and that the immediate rates of return may not be as lucrative as that of finance or crypto. That said, I believe there will be an explosion of new technology firms in a few quarters, spurred on by the supply chain crisis, an increase in funding, or the recent misfortunes of the industry that point to a need for technology.

The biggest problems are systemic, and related to the fact that building software (or hardware) in shipping requires companies to solve multiple zero-to-one problems with no common solution. Here are some I have encounted, and why they persist.

One of the biggest strengths of shipping - in fact the very thing lending it resilience - is also one of its biggest problems. Maritime trade has been fundamentally decentralized for centuries, long before crypto made decentralization the mot du jour.

Vessels are floating nations in their own right, with crew and cargo that comes from and goes all over the world. Involved in the daily operations of a single vessel at rest are often six or seven different companies, with just as many countries and regulatory bodies. In motion, that number goes up considerably, and navigating this landscape could very well be a sector of its own.

To form a coherent picture of a single vessel, multiple companies and countries need to share data - something the industry has been traditionally resistant to. This is a big reason most new companies are forced to focus on prediction and estimation, rather than work with real information.

Internal digitization in industries often happens in waves. There is usually the first wave of custom, purpose built software to solve specific issues with expensive machines, followed by a second wave of general purpose tools (think Excel and email) that improve everyday tasks. Next comes a the management-led wave of internal integration, where custom tools are once again commissioned by separate departments to digitize their workflows. As these systems reach their end-of-life, an unbundling can take place, with externally built single-purpose software taking the place of these systems.

Each wave happens as workflows build up inefficiencies to push companies over the hill of spending differently. Enough dissatisfaction with the way things are needs to exist in order to bridge the loss in productivity that comes with trying something new.

With each change, the pattern often swings from externally-built to internally-commissioned. Unfortunately there is no ideal solution: bespoke workflows will always fit better when internally directed, but external vendors can aggregate learning and innovation across multiple players to deliver a superior product.

Maritime is still in the third wave, with early adopters looking ahead. The problem is that there are currently very few standards for data interchange, as most existing pieces were built in siloes for individual consumption.

Greywing might be a prime case to see how diverse things are. As of this piece, we connect to 20-30 different companies, and at least twice as many data sources. Our integrations cover simple JSON push and pull APIs, SOAP, sockets, and even xlsx files that are periodically downloaded and parsed.

Most information in maritime still originates from manual entry, and is maintained on an honor system that presumes you're being honest. AIS - the underlying technology for tracking vessels on their journeys - is self-reported, as is the data for any ports or offshore anchorages that aren't big enough to qualify for an UNLOCODE. The same vessel - or port - can have multiple names and attributes, and it's often hard to tell what the right information is.

Correct information turns out often to be the wrong way to think about this data, which needs to be cleaned and coalesced before it can be of any use. Some companies like Spire provide the valuable service of cleaning this data as they provide it, but the output can only be so clean.

What this means is that failure-tolerance and some level of probabilistic modelling need to be worked into any system that consumes maritime data. Some of our internal systems have already moved in this direction, using multiple data points to look for consensus with some level of confidence.

Software interfaces in shipping have yet to find an equilibrium, with the fundamental interface primitives for the industry not having been designed yet. Like smartphones in the early 2000s, or ridesharing apps at the very beginning, interfaces are still experimental (or worse, ancient), with no real connection to the underlying information or the users in front of them.

Most interfaces in shipping look exactly like the things they replace - spreadsheets. This makes complete sense when attempting to replace a workflow built on spreadsheets, as it involves less training for users. However, this can also hold back progression, as it takes a fair few cycles of iteration before other primitives can take hold and perform on par or better.

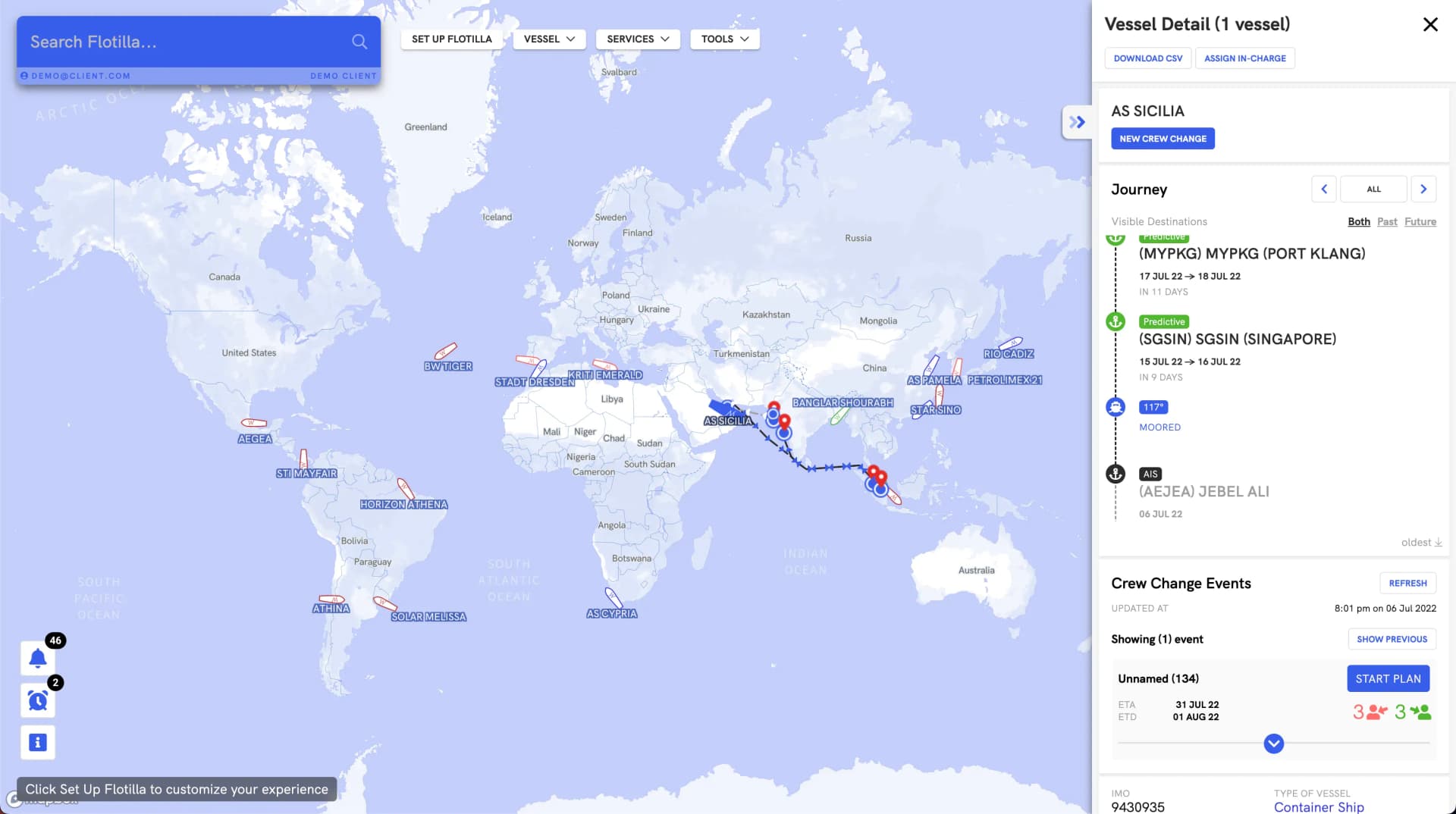

We are taking a big risk by making the map our base primitive, and building a new interface for crew changes that relies on contextual visual representation - show not tell - and cutting down information when unnecessary. I wrote about button syndrome some time ago, which turned out to be quite polarising. Users are often split between power users who hate a loss of control, and others that would like less information overload on their screens.

I expect these to be the formative years of shipping interfaces, and the companies formed this half-decade will be the ones defining it.

I expect these to be the formative years of shipping interfaces, and the companies formed this half-decade will be the ones defining it.

This is one of the biggest hurdles we've had to solve. Maritime is simply missing a lot of the base tooling that we take for granted in other fields.

A good example - among many - is routing. Most data in shipping is closely tied to a vessel's route, which can be a complex path between two ports. Ships prefer to use highways when possible, to avoid congestion and increase speeds in deeper water, which makes straight-line paths often the least efficient. Yet most platforms today still use straight lines to convert port calls to a route, or skip this process altogether.

Almost every company that does have routing has had to build it in-house, as have we. We might soon see startups that focus on these individual problems - as there already are - and try to deliver a general-purpose solution to each one. Further unbundling might be ahead of us.

Despite these problems, shipping can be an exciting place to work, for one big reason.

Some of the most interesting problems are zero-to-one problems. It can be hard to get them right, and only time will confirm your hypotheses, but they allow for creative solutions that have the potential to redefine how we do things.

The problems of maritime are sometimes hard, but they are not new under the sun. They are the same problems faced by every industry as we try to find new ways to do things that were better than before. A path lined with just as many eureka moments as there are setbacks, I'm happy to be solving them every day. What has been repeatedly clear, is that there is not a boring day in sight for quite a while.

We release every week.

Learn about new tech in maritime, and what we've built as soon as it's live.