Building a sharded queue for processing rate-sensitive jobs across multiple servers

Hrishi Olickel

Published on 20th Aug 2020

12 minutes read

Some time ago, we needed an interval queue (something that can queue jobs and run them at a rate limit) for async (or promise-based) functions in Javascript. We built a pretty simple system that did the job well and introduced no dependencies, and open-sourced it here.

Along the way, we made some optimizations, like adding requeing for failed jobs. However, as our systems grew in size and complexity, we quickly outgrew the initial system. We needed a queue that could function across multiple servers and instances without losing the rate and execution guarantees we needed.

The initial queue does not work in a cluster, multi-process or multi-threaded environment - something I kept putting off due to the complexity. While the original queue was simple in theory, the basic concept of getting an interval queue to work with multiple shards is non-trivial - there are multiple ways to do it, each with their own trade-offs. Here's our analysis of the problem and the eventual solution we arrived at. We've open-sourced the project since then here, and we're happy to see it used in the wild.

The easiest way to build any parallel system - and the worst way - is to not have a clear idea on what you shouldn't do. What behavior is expected? What is no good? What properties should the system always satisfy, even in intermediate states? What properties are loose and some violations are okay?

Like I said, there's multiple ways to skin this cat. The constraints I've chosen fit my application best, and allow for future expansion into projects I want to use this in. To that end, some of them may not fit what you're looking for, but I hope the analysis is helpful.

In our sharded version of the queue, there are few properties we want to get right:

n is the number of shards, the queue must survive up to n-1 failures.The last property may seem strange or against the thesis of a parallel queue, but it allows us to simplify the implementation without sacrificing performance. The point of a sharded interval queue is not to run jobs in parallel, but to synchronize execution across distributed shards. This also shouldn't have any issues with performance - for any queue, doubling throughput simply means halving the interval time of the queue.

We also have a few softer constraints that will serve as principles: 6. Prefer simplicity of implementation. 7. Prefer lighter resource utilization. 8. No time travelling in shared-state, i.e. no backwards jumping.

Now that we have some idea of how the system should behave, we have a few compromises that we'll make for the sake of these principles and my sanity.

First, we'll keep the queue leaderless. This means that all the shards run the same logic with some central persistent storage to communicate. Having a leader will solve some problems - we don't have to work out whether some operations are atomic, we can modify properties without having to reach consensus, and add priorities to shards. However, leader election is complex (as the people behind PBFT and RAFT can tell you). Satisfying 4 in a leader-based system would mean checking for leader failure, implementing some form of election and making sure that there is always one leader that is executing. We have the advantage that we can assume none of our shards are malicious, but network partitions are still a problem and it's something I expect this queue will have to deal with later on. For now, our shards are left leaderless to fend for themselves.

The second - which I expect to be a bit more contentious but hey my queue my choice - is to keep the queue from having a persistent interval running in the background. This is where 7 and 6 come into conflict. Having a persistent interval within each queue that checks to see if it can run jobs is simpler from an implementation perspective, but heavier on resources. In addition, given that this queue won't always be run on systems that are owned and operated by me, I'm uncomfortable with the prospect of custom event loops starting themselves in someone else's code and throwing unpredictable orphaned exceptions. Keeping the system predictable - same as in the original single-threaded implementation with queue.start and queue.add causing executions - seems to be the better solution. Each queue shard will shut itself down when it has no more jobs to run, and will start back up when a job is added.

An additional compromise here that you'll notice is that the shards can't all be unpaused at the same time. You'll notice now that I was a little sneaky and made sure that constraint 3 only said pause-able. The problem with having neither persistent intervals nor leader is that the queues have no way of knowing when to start back up. That said, this is a problem that can be easily solved from the outside of the queue - with a persistent interval function. I'd much rather it was your function than mine, so this is all right.

While we're talking about compromises, let's talk about some of the benefits of these choices. The first is from having no leader. If you only use shared state to communicate, the speed at which each shard can operate is only limited by the speed of that shared state, and the state is under your control. As you'll see in the final implementation, this means that you can use a simple JSON file for shared state and have it be easily inspectable and debuggable, switch to Redis for a significantly bump in speed, or even roll your own without much effort.

The second is that having the queues stop executing when they're empty means that they can be closer to a drop-in rate-limiting replacement. If executions are common the queues will stay active, but if you only have quick bursts of execution spaced out by hours or days, there's no ongoing code that will trip you up.

Finally, these constraints allowed me to keep the final implementation free of other dependencies and therefore a little less prone to code rot, especially with Node's speed of update. You can copy the code into your own, run it client or server-side, and you're not working with moving targets and security bugs from the dependencies of my dependencies.

Now we have n shards and some shared state between them, the primary entry point for each shard is when a job is enqueued. The key question that needs to be answered is:

When do I run this job? If we can answer it in a way that makes sense for all the shards, we're done (well we're not exactly done, we're left with the implementation, which is it's own bag of cats but let's ignore that for now). We'll look at some of the ideas I considered, but if you'd like you can skip ahead to the one that won out.

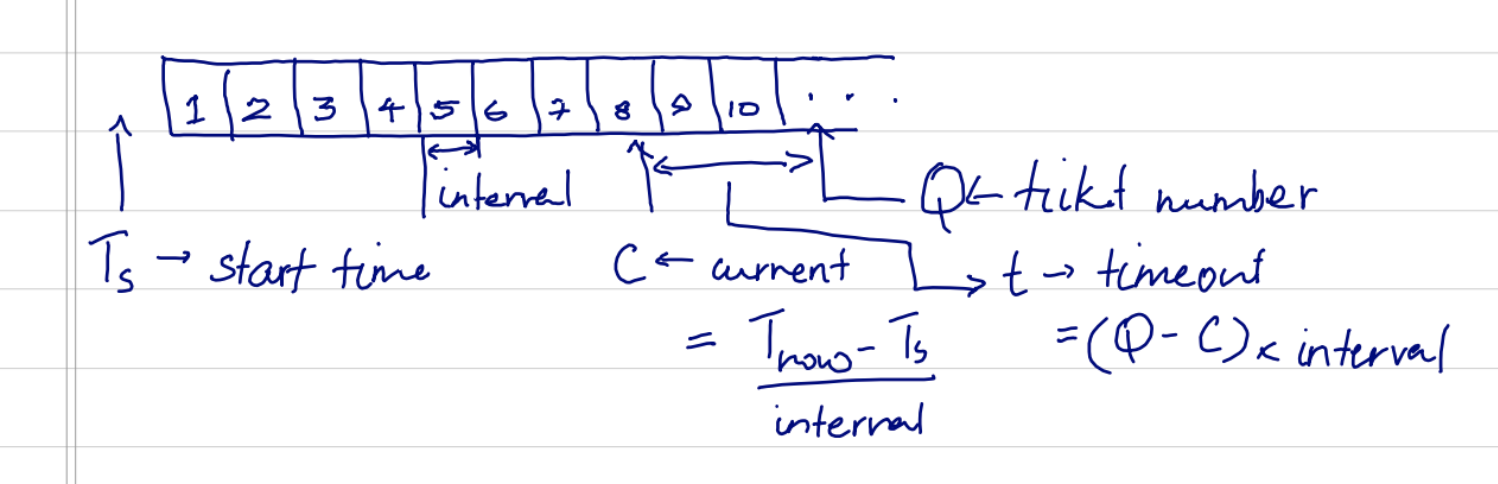

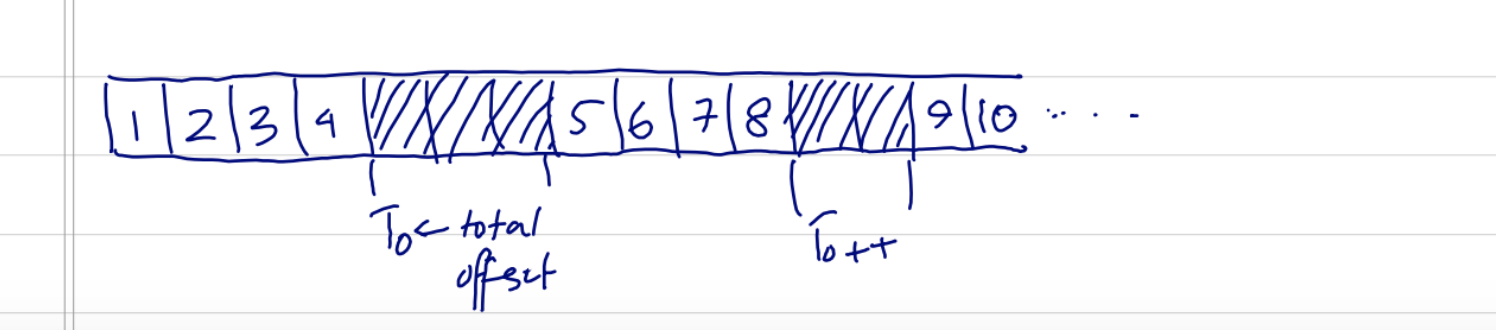

The key is in how we represent items in the shared state. Since we want the queue to be a general-purpose job queue, we can't exactly serialize the jobs and save them to shared state. Each shard keeps it's own list of jobs, and runs them at the right time. One way of doing this is to have a ticket number. Each shard collects and increments the ticket number and assigns it to its job. This satisfies 1, if we assume that the increment is atomic. Now, how we do know when to run the job?

If the queue is always running, this is simple. If we store the time when the queue was started, we can derive the current position of the queue by subtracting it from the current time and finding out how many intervals have passed. Once we have the current position, we know how long we need to wait to run the job that was just added. This is simple, and can survive multiple shards failing. Those timeslots will be unclaimed, but that is a fair loss. Simple.

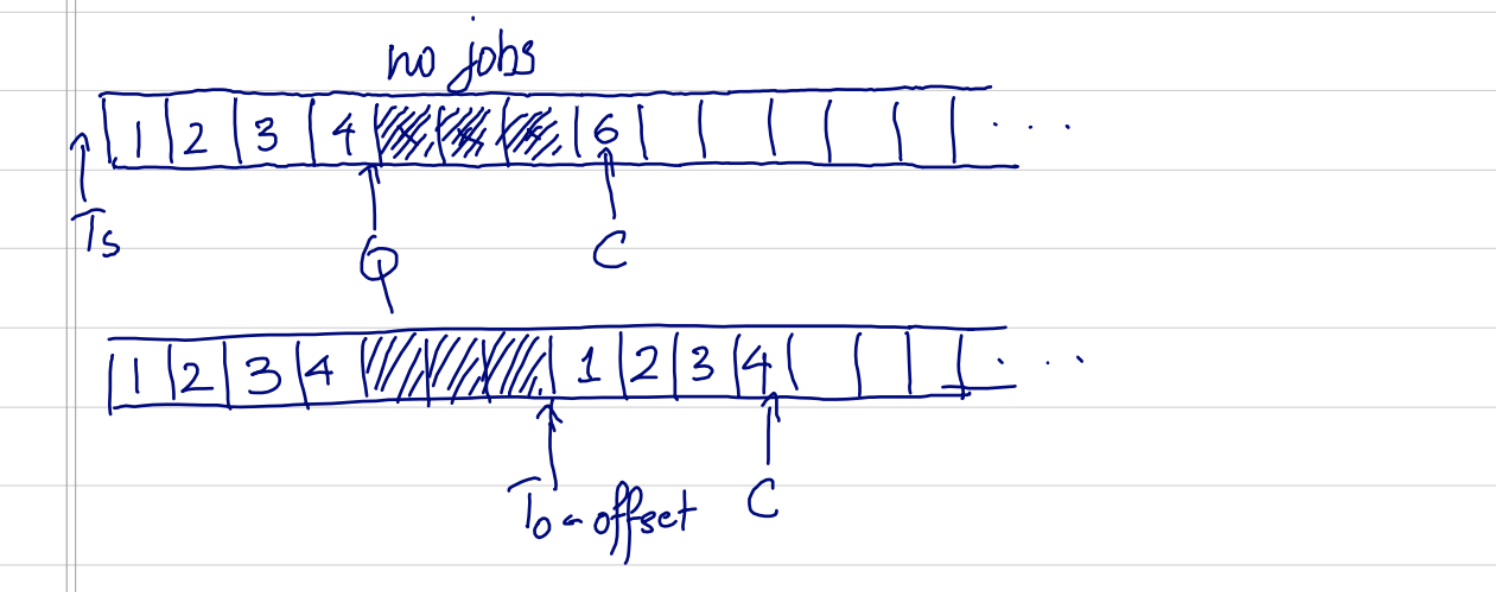

The problem is when the queue stops running, or there aren't enough jobs in the queue to keep ticking over the ticket. The system fails when the ticket falls behind the current queue position, which will keep moving regardless. One way to solve this is to add an offset time. If you find that the queue hasn't been issuing tickets for some time (i.e. ticket number < queue position), we can "restart" the queue by updating the offset. If we include the offset in our calculation of the ticket number, we'll have a queue position that is either valid or can be revalidated.

This is a solution I was stuck on for some time. I consulted some of the smartest people I know, trying to find out how they would do it, but it always came back to some version of this idea. One suggestion was to keep the queue position as a separate value in shared state and have the jobs increment it as they were started. No start time or offset. You had a ticket number that worked similarly, except now you would set ticket number = queue position if ticket number < queue position. This works well, but violates 1 and 2 and is essentially another way to represent the initial solution.

It's still a viable option, since you could derive a job number that doesn't violate 1 and 2 from the ticket number and queue position if you keep an offset variable that counted the total amount the ticket number was pulled forward.

It was largely a problem of getting lost in the first solution you think of. I was pretty close to implementing it, but it just didn't feel right and had some problems. First, having an offset variable updated by any possible shard added another variable where concurrency was an issue, except this time it wasn't an increment but an arbitrary update. I was lost in the math for a bit and had a solution where I could keep possible queue syncing issues to 2x the total interval, but it was a complicated implementation that I couldn't be sure was right.

The other problem was in the possible implementations. With this branch of solutions, you had to start the job (in a setTimeout to the right interval) as soon as they came in, which meant that it was heavier on resources and the Javascript job queue. If you didn't, and the queue was paused or the offset updated in the time it took for the job to start, you would get a different value for expected time of execution. You could solve this by annotating each job in local state with the time it was meant to be run, but at this point it started feeling like a tower of duct tape. There's got to be a simpler option.

The final solution took me an embarrassingly long time to see, and I'm quite sure most readers will already have been screaming at me that there's a simpler way. Sorry about that, and I submit there's a good chance of a better solution being out there, so if you think this sucks please let me know. Here's what I ended up with.

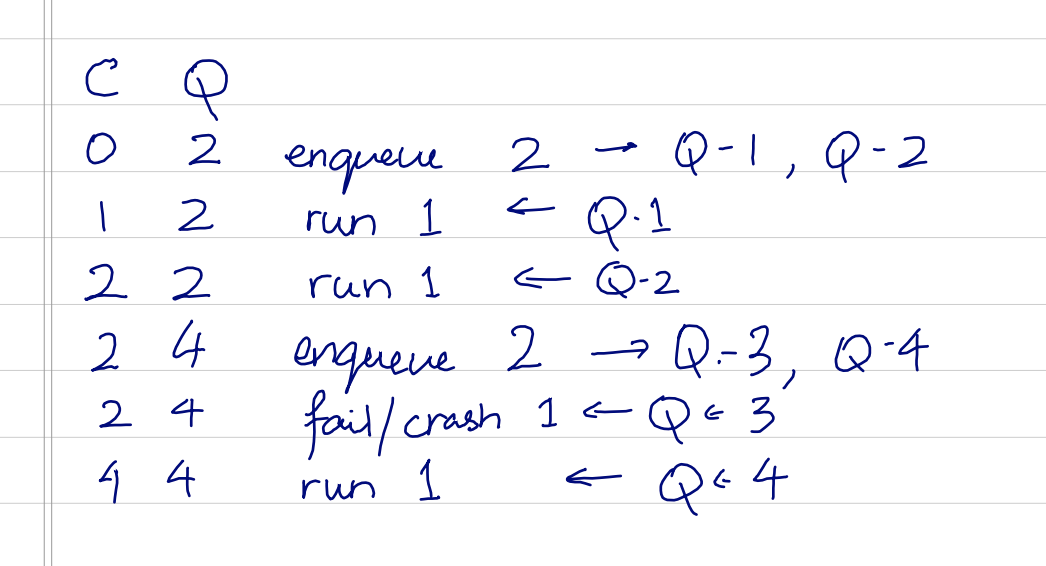

We only have two mutable variables in shared state - ticket, which is the current ticket number and current, which is the current queue position. Each shard schedules one job at a time, scheduling the next job for later when the current one is started.

When enqueueing a job, each shard will take and increment a ticket and enqueue the job with that ticket to its local queue. The timeout is determined by the difference in ticket numbers between the currently running job and the one being scheduled. When a job is being run, the current number is incremented and the next job is pulled up. If the current number is behind the executing ticket number, it is set to the ticket number.

As we can see, the values of C and Q stay valid even with failures. With this method, we limit most of the operations to an increment. In the case of a failure the next running job will restore a valid state to the queue. This also makes pausing queues easy, since there is only ever one job per shard in each JS event queue.

If we had all the jobs scheduled together, pausing them can get complicated. All the currently scheduled but not started jobs need to be stopped, and the internal state needs to reflect this. Now that we only have a single job scheduled at any one time, pausing it becomes pretty simple.

We still need to deal with unpausing, which is now simpler. When an unpaused job is being scheduled, we can tell if the queue has already passed its execution spot. If it has, the job is requeued the same way we add a new job, and the jobs which still have valid execution spots continue to run.

This mostly concludes the theory part of things. The implementation poses its own challenges, which I've covered in a longer post here.

However, this is by no means a true conclusion of the theory. I'm sure there are possible issues with this way of doing things, and better ways out there, and we continue to improve the system with user input.

Want to stay updated on all things AI we're building for Maritime? Sign up to our monthly newsletter here.

We release every week.

Learn about new tech in maritime, and what we've built as soon as it's live.